Famines, Gendered Violence and Nationbuilding: The Australian Experience

- Nov 13, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 10, 2020

Swati Parashar | 13 November 2019

Famines and hunger deaths are often considered a thing of the past. Although there is some media coverage of the hunger and famine mortality of children in the ongoing civil war in Yemen, most people assume that, like the epidemic diseases that wiped out populations, famines are afflictions of historical eras. People widely assume that these famines of long ago were caused by massive crop failures and the inability of people to access food. Several superstitious beliefs have persisted about famines as nature’s or God’s punishment of a population steeped in vices. Labelled as ‘natural disasters’, ‘food insecurity’, ‘food scarcity’, ‘hunger crises’, or ‘drought’, no identifiable human agency can be easily held accountable for famines as mass atrocities and acts of political violence against vulnerable populations. Portrayed also as death and suffering that occurs in the gendered household, famines are not usually considered ‘public’ crimes, and perpetrators, if any, are remote.

This picture could not be further from the truth and is maintained by the global spotlight on war-related gory deaths, injuries, and displacements. Bodily injuries that keep 24X7 media channels and viewers occupied, represent blood, war, and precipitous deaths (on a temporal scale). Slow starvation of emaciated bodies, deaths, and displacement that occur due to hunger, rarely make the news. When famine is reported, there is a ‘feminization’ of famine-related violence, visualized through emaciated, frail, unaesthetic, shrinking bodies (usually of women and children) waiting for imminent death. Famines, unlike wars, have no heroes, victims, or witnesses that can tell stories of courage, valor, victories, and survival. In many contexts the stories of famine and hunger deaths are stories of shame and emasculation, not to be repeated by future generations. Some famines are remembered and commemorated widely by diasporic populations and succeeding generations (e.g.: The Great Hunger, Ireland; and Holodomor, Ukraine); others are consigned to the silences and erasures of history (e.g.: Ethiopia Famine; Somalia Famine). This selective remembering and forgetting of famines also involves colonial histories of gendered political violence and nationbuilding through famine crimes.

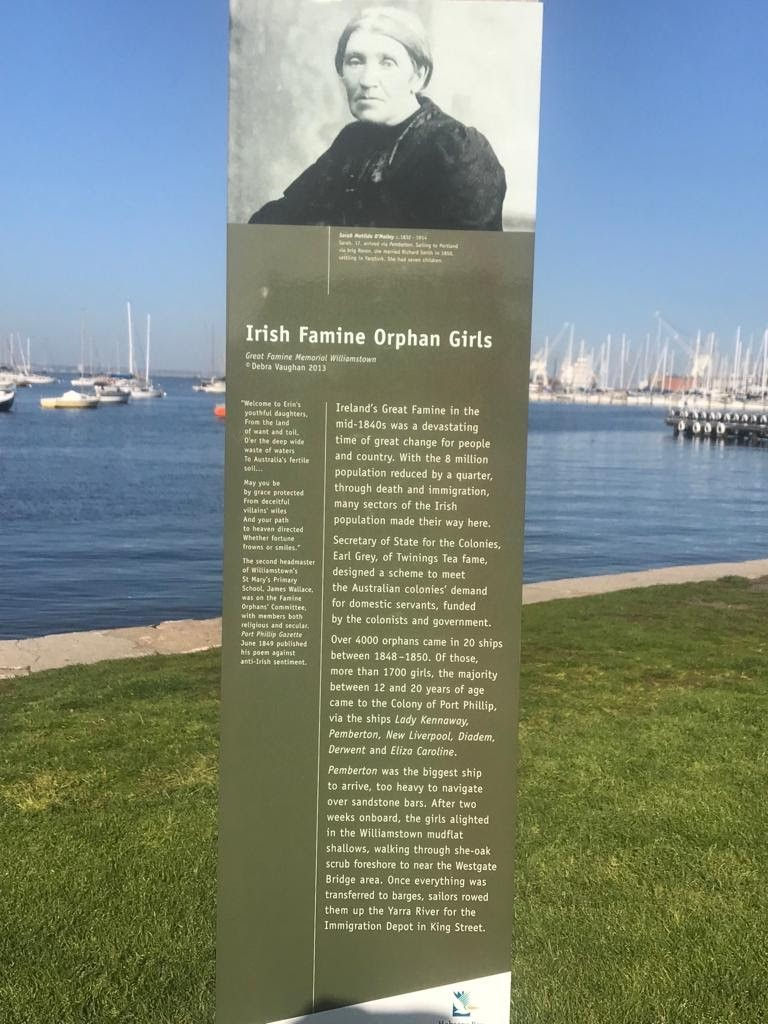

I travelled to Australia recently, visiting the Famine Rock Memorial in Williamstown, Victoria, and the Famine Memorial Installation at Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney. Both of these commemorative structures of the Great Irish Famine (1845 to 1849) remind us how race and gender play critical roles in nationbuilding projects in settler-colonial societies. The bluestone rock in Williamstown marks the 150th anniversary of the arrival of 191 girls onboard a ship to Hobson’s Bay, Australia. The artistic memorial in Sydney not only points to the suffering household during the Irish Famine years but also celebrates more than 4000 Irish women and girls, famine survivors who were brought to Australia to contribute to the nationbuilding enterprise. The Earl Grey scheme was devised by the British colonial government to settle Irish famine orphans (women and girls) in the new Australian colony. Their job was to marry the ‘convicts’ and bear children to populate the Australian colony. It is unsurprising that Irish orphan girls were considered more suitable to reproduce for ‘white’ Australian nationhood, especially since British women did not demonstrate a keen interest in emigrating to settle down with male convicts. Irish girls and women were preferred not just for their embodied ‘whiteness’ but also because they carried with them moral values of ‘virtue’ and ‘purity’ derived from their Catholic religious faith.

Thus, more than 4000 Irish female immigrants, most of whom were famine survivors, made the arduous journey to participate in the Australian nationbuilding project. The Famine memorial website notes that the monument in Sydney recognizes the success of the women ‘and their contribution to the building of this great country’. The names of these girls and women are inscribed both on the glass wall of the Sydney monument and the remembrance plaque opposite the Williamstown Famine Rock. The website has some recorded details of their lives, their places of origin, ages, the ships they sailed on, and their employment and marriage details in Australia. There is something incredibly poignant about being famine survivors in a colonized country, shipped over to a foreign land as a 'solution' to the skewed sex ratio, mostly as an act of charity, and then serving as domestic workers in indentured contracts and bearing children with white immigrants (mostly convicts) to enable the idea of settler-colonial Australia. The Williamstown Rock Memorial also recognizes the dispossession of aboriginal Australians, on whose land and through whose resources, white settlers created the racialized hierarchies of Australian nationhood.

That, nations are created and sustained on the suffering and brutalized bodies of women is well documented by feminists. Celebrating famine survivors as some sort of heroines who contributed to nationbuilding should remind us of the Bengali 'Birongonas', or the women raped during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. Public acknowledgement of their national 'sacrifice' was rendered through the term 'birongona', or 'war heroines' who deserved the highest respect and honour for their suffering/contributions during the birth of the new nation, i.e. Bangladesh. I am not equating the suffering of famine affected women and the sexual violence survivors of war, but it cannot be denied that nationbuilding and violence on women’s bodies are intimately linked in many different contexts.

Any nation/empire building enterprise is further gendered where the reproductive labour of women counts, literally and figuratively. Australian nationhood is even more so, built on the reproductive labour of some of the frailest and most vulnerable survivors of the Great Irish Famine. The documented stories of women and girls who survived the Irish Famine and travelled to Australia, hardly do justice to their lived experiences of religious patriarchy, colonial melancholia and gendered abuse and suffering in famine-related violence. The stories of these women clearly suggest that famines need to be studied as ‘public’ crimes with grave consequences for victims and survivors. The complicity of various actors needs to be investigated and highlighted in the pursuit of ‘truth’ and reparative justice not just restorative forgiveness. As our project progresses, we hope to investigate the gendered violence, vulnerability and racialized nationbuilding inscribed upon hunger-affected, emaciated bodies that either die or barely survive a slow and torturous death, on a temporal landscape.

Keywords: #Australia, #famine, #gender, #GreatIrishFamine #memorials, #nationbuilding, #Ireland #Feminism #Ethiopia #Somalia #BengalFamine #FamineRock #HydePark

Swati Parashar is Associate Professor in Peace and Development, School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg. She is currently co-investigator (with Camilla Orjuela) on a Swedish Research Council (VR)-funded project on Famines as Mass Atrocities: Reconsidering Violence, Accountability and Memory in Relation to Hunger (2019-2023).

Comments